This guide starts with the basics of what fixed income investments are and expands to explain how bonds are priced, how credit rating agencies grade bonds and how best to cost effectively invest in fixed income investments.

What are fixed income investments?

Fixed income investments are debt investments where you are effectively loaning money either to Governments (gilts or gilt-edged securities, also known as treasuries or sovereign debt) or companies (corporate bonds).

When you make a fixed income investment in a gilt or corporate bond, the lending Government or company typically agrees to pay you a fixed rate of interest over a fixed loan term, with the original balance loaned repaid at the end of the fixed period (a.k.a. the redemption date).

Making money with fixed income investments

Investors in gilts or corporate bonds can profit via income payments and rising prices:

Income payments

Both gilts and corporate bonds traditionally pay a fixed rate of interest on a semi-annual basis. A £100 5% corporate bond would pay coupon interest of £5 a year (£100 par value * 5%). For example, if paid semi-annually, this might pay £2.50 in January followed by £2.50 in July.

However, when private investors purchase gilts or corporate bonds, they will rarely purchase at par value (also known as face value). This is because bonds are typically purchased on the open market after they have been issued, where prices can vary from day to day. For this reason, investors often talk about ‘income yield’ rather than coupon rate when discussing bonds.

Whereas the coupon rate is fixed interest divided by par value, income yield is fixed interest divided by the current bond price. For example, if the £100 corporate bond price rises to £105, the income yield would be lower than the coupon rate at 4.76% (£5/£105).

Rising prices

Bond prices on the secondary market can fluctuate (both up/down in value) for a number of reasons:

- Change in interest rates – If the income yield on a given bond is higher than the return available to investors from other investments or savings, then the the price of the bond will generally rise, driving the yield down.

- Changes in deemed risk – Where a credit rating agency such as Moody’s, Standard and Poor’s or Fitch changes its opinion on the risk of a particular bond, this will impact the price of the bond. If the rating is improved, this will increase the price. Conversely, if the bond is downgraded, the price will decrease as investors will require an increased yield to compensate for the increased risk. The level of deemed risk could be impacted by business performance even where bond rating remain stable. See ‘how bonds are graded‘ section below.

- Time left to redemption – As a bond gets closer to its redemption rate, the price tends to get closer to the par value (as this is the value at which the bond can be redeemed at maturity).

- Inflation rate – If inflation rises, bond prices will generally decrease. This is because both the fixed interest payments and ultimate redemption amount will be worth less in real terms. As inflation means that money is worth less in real terms, investors generally expect higher percentage returns to offset its impact.

- Supply and demand – As bonds are traded on the secondary market, an imbalance between the volume of willing buyers and sellers can cause bond prices to move.

- Liquidity – A bond which is frequently traded will be more attractive to an investor as it means it would be easier for that investor to extract their cash if required at a later point in time. Generally, if a bond is more liquid, the bid/ask prices will feature a narrower spread.

Changing bond prices – a worked example

Imagine a 20-year 5% corporate bond priced at £100. In 20 years time, this bond will redeem at £100. However, between then and now, the price will shift due to a mix of micro and macro economic factors as outlined above.

| Price | Yield |

|---|---|

| Price equals par value | Yield equals coupon rate |

| Price above par value | Yield below coupon rate |

| Price below par value | Yield below coupon rate |

Impact of changing interest rates on bond prices

If interest rates increased to 9%, investors could put £100 in the bank to generate £9 annual interest. Since saving that £100 in a bank is less risky than owning a bond, the price of our £100 bond would need to decrease to entice investors to purchase. The bond would need to fall to £55.55 just to provide an equivalent income yield (as £55.55 * 9% is £5). The price would then be below the par value, but the income yield would be above the coupon rate.

Impact of changes in deemed risk on bond prices

If the business issuing the corporate bond reports a fantastic set of results, resulting in an improved credit rating from Moody’s, investors may decide that a yield of 4.7% is sufficient to reflect the risk of holding the bond. The price of the bond could now rise to £106.38 (as £106.38 * 4.7% is £5). The price would then be above the par value, but the income yield would be below the coupon rate.

Conversely, if the business posts a poor set of results, resulting in a downgrade in rating from Moody’s, investors may decide a yield of 8.0% would be commensurate to the level of increased risk. The price of the bond would have to decrease to £62.50 (as £62.50 * 8.0% is £5).

What is redemption yield?

Until now, this article has focused on income yield. However, redemption yield is actually a more accurate measure of yield which takes into account the fact that a capital/gain loss is likely to be made where the bond has not been purchased at par value. Given the majority of bond investments are made via the secondary market, it is far more common for a bond to be purchased at a price above or below par, than at par value itself.

Redemption yield may also be referred to as ‘yield to maturity’ or ‘book yield’.

| Current price vs. par | Redemption vs. income yield |

|---|---|

| Bond price less than par value | Redemption yield higher than income yield |

| Bond price more than par value | Redemption yield lower than income yield |

Where the current price of a bond is lower than the par value of the bond, the redemption yield percentage will be higher than the income yield.

Conversely, where the current price of a bond exceeds the par value of the bond, the redemption yield percentage will be lower than the income yield.

Other bond yield calculations

Whilst the most common yields referenced are income yield and redemption yield, you may also come across yield to call or yield to worst when dealing with callable bonds.

How are bonds graded?

The big three credit ratings agencies are Moody’s, Standard and Poor’s (‘S&P’) and Fitch. All of these entities are regulated by the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA), though regulatory responsibility will pass to the FCA in the UK once the transition period for leaving the EU has come to an end.

The role of these firms is to assess and grade the ability of bond issuers (countries or Corporate entities) to meet their obligations. Each of these agencies have their own ratings scale, though they are broadly comparable as shown in the table below.

| Grade | Moody's description | Moody's | S&P | Fitch |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Investment grade | Highest quality, lowest credit risk | Aaa | AAA | AAA |

| High quality, very low credit risk | Aa1 | AA+ | AA+ | |

| Aa2 | AA | AA | ||

| Aa3 | AA- | AA- | ||

| Upper-medium grade, low credit risk | A1 | A+ | A+ | |

| A2 | A | A | ||

| A3 | A- | A- | ||

| Medium grade, moderate credit risk with some speculative characteristics | Baa1 | BBB+ | BBB+ | |

| Baa2 | BBB | BBB | ||

| Baa3 | BBB- | BBB- | ||

| Speculative grade (high yield / junk bonds) | Speculative, substantial credit risk | Ba1 | BB+ | BB+ |

| Ba2 | BB | BB | ||

| Ba3 | BB- | BB- | ||

| Speculative, high credit risk | B1 | B+ | B+ | |

| B2 | B | B | ||

| B3 | B- | B- | ||

| Speculative, very high credit risk | Caa1 | CCC+ | CCC | |

| Caa2 | CCC | CC | ||

| Caa2 | CCC- | C | ||

| Highly speculative, likely to be in, or very near, default. Some prospect of recovery of principal and interest. | Ca | R | DDD | |

| Typically in default, with little prospect for recovery of principal or interest. | C | SD | DD | |

| In default on all long-term debt obligations | D | D |

Credit rating analysts look at factual data points including leverage, coverage, liquidity and profitability measures, as well as subjective measures such as the quality of management, to assess the likelihood of default/loss. Comparisons are made using historical experience of default/loss to classify current bonds into ratings categories.

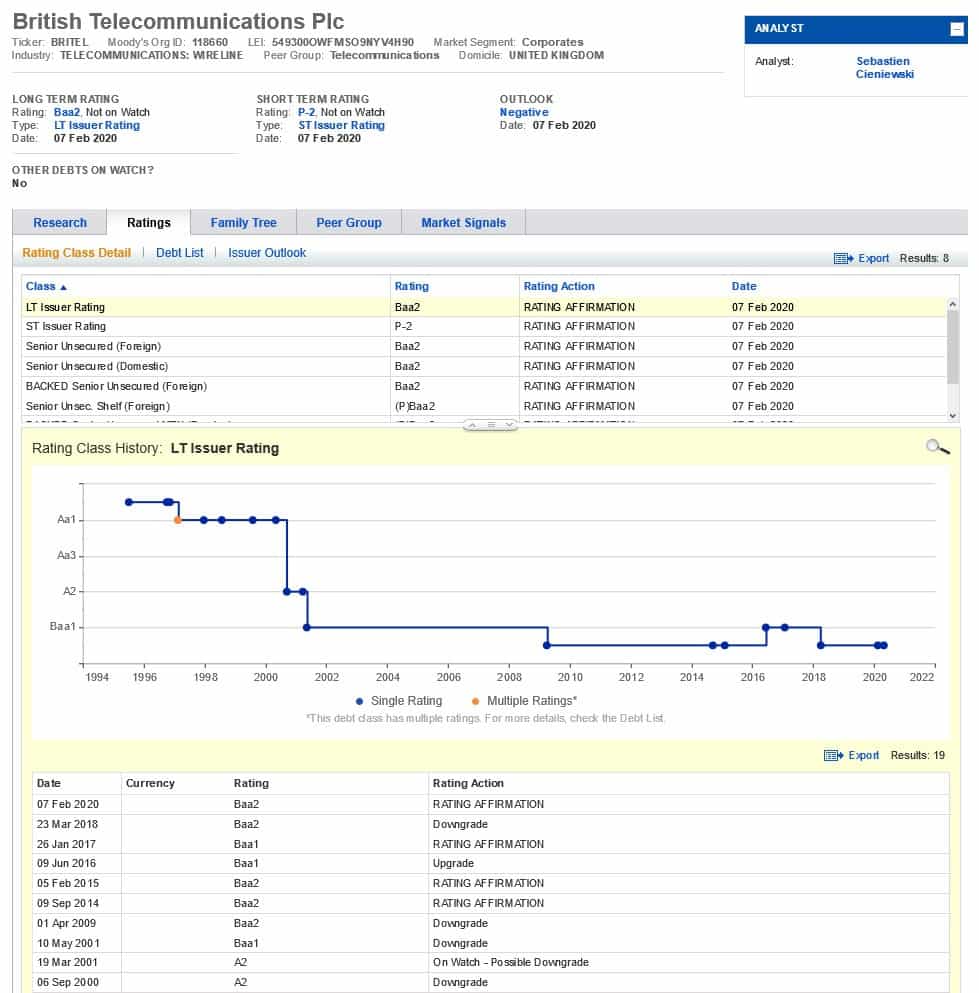

You can view credit ratings by registering with the credit ratings agencies such as Moody’s and searching for the relevant company name or the bonds International Securities Identification Number (‘ISIN’ code). Below is an example credit rating report from Moody’s for BT, which shows that BT were previously rated Aa1 by Moody’s in 1996, but that this rating has fallen to Baa2 with a negative outlook in February 2020. A negative outlook means that Moody’s believes that BT’s credit rating might be lowered in the medium-long term.

Are there different types of gilts and corporate bonds?

Yes, there are multiple types of both gilts and corporate bonds. The most common types of each are outlined below.

Gilts

There are two different types of gilts: conventional gilts and index-linked gilts.

Conventional gilts

The majority of the gilts issued by the UK government (c.75%) are ‘conventional gilts’ which pay a fixed coupon rate every six months until a specific maturity date, at which point the holder receives their final interest payment and their original principal. Conventional gilts are typically issued for periods of 5, 10, 30 or 50 years.

Index-Linked gilts

Rather than a fixed coupon rate, holder of index-linked gilts receive semi-annual payments which vary in accordance with the Retail Price Index (‘RPI’). For example, the Treasury 0.125% 2068 GILT would pay 0.125% plus the movement in RPI.

Corporate bonds

By grading

Investment grade bonds

Investment grade bonds are those rated BBB or above, as shown in the ‘how are bonds graded’ section above. Generally, investment grade bond offers more security but lower profit potential than high yield (or junk) bonds.

Speculative grade bonds (high yield or junk bonds)

Speculative grade bonds (often called high yield or junk bonds) are those rated below Baa/BBB by Moody’s or S&P/Fitch respectively, as shown in the ‘how are bonds graded’ section above. These bonds typically feature shorter maturities than investment grade bonds. They tend to offer less security but higher profit potential than investment grade bonds.

By type

Vanilla bonds

A ‘vanilla’ bond is a bog-standard bond without any unusual features. It features a fixed coupon rate, defined maturity date and is issued/redeemed at its par value.

Floating rate bonds

Whereas standard vanilla bonds pay a fixed coupon rate, floating rate bonds pay variable amounts of interest linked to market interest rates. This gives rise to potential higher or lower income returns as rates rise or fall.

Zero Coupon

Zero coupon bonds make no periodic interest payments (i.e. there is no income). Instead, investors can profit by purchasing the bonds at a discount to face value, which can be redeemed in full at maturity.

Convertible bonds

Convertible bonds feature typical bond characteristics but also include an option to convert the bond investment into equity of the underlying company.

Perpetual bonds

Perpetual bonds feature no maturity date, meaning they continue to pay the coupon interest in perpetuity.

PIBS

Permanent Interest Bearing Shares (commonly known as ‘PIBS’) are a type of bond issued by UK building societies. They are subordinated debt and rank lower than customer deposits and senior bonds in the event of liquidation. PIBS are similar to gilts and corporate bonds in that they pay a fixed interest coupon rate, though differ in that they do not feature a fixed redemption date. Instead, most PIBS feature ‘call’ options which allow the issuer (i.e. the building society) to repurchase the bond at par value on specified dates. This ability to repurchase the bond is a right rather than an obligation, hence the use of ‘Permanent’ in the name. If the PIBS are not repurchased at the specified date, the coupon rate payable typically falls to a lower pre-set rate.

Other bond types

In addition to the above, there are a number of less common and/or more complex types of bond, including:

- Step up bonds

- Step down bonds

- Inverse floating rate bond

- Participatory bond

- Income bonds

- Payment in kind bonds

- Extendable bonds

- Extendable reset bonds

- Foreign currency convertible bonds

- Exchangeable bonds

- Callable bonds

- Puttable bonds

Capital structure / bond security

Bonds can be both secured (i.e. specified underlying assets are assigned to the bond and could be sold in the event of default) or unsecured (i.e. no underlying assets assigned to the bond).

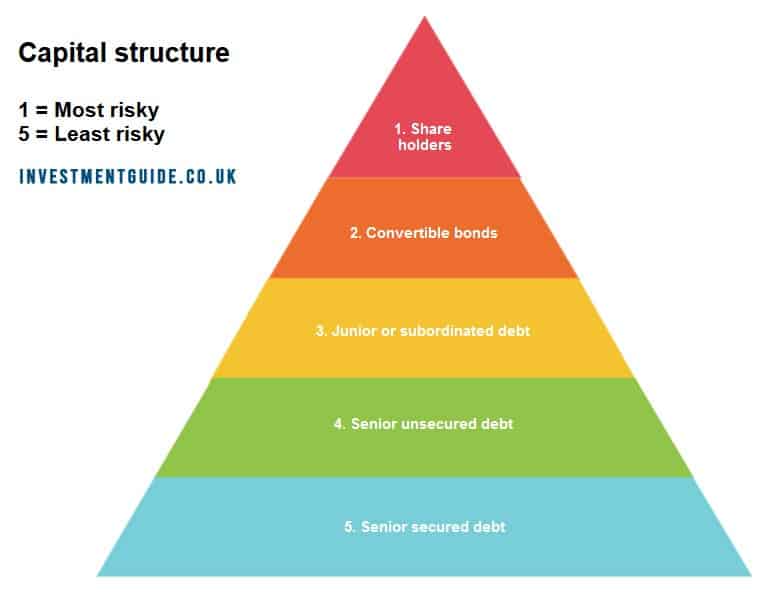

Before investing in bonds, you should understand how the capital structure of a business works. Different types of stakeholders will take different positions in the queue for return of capital in the event that the company goes into administration:

- The least risky type of investment in a company is in senior secured debt (i.e. a loan or bond secured against underlying assets). Investors in senior secured debt are paid first.

- Next in line is senior unsecured debt which is still lower risk than junior or subordinated debt, but which has no assets held as collateral against the loan or bond.

- Junior or subordinated bond holders would be paid after the holders of senior bonds have been paid.

- Investors in convertible bonds have a lower rank priority claim on assets than investors in non-convertible bonds.

- Finally, equity shareholders take on the greatest level of risk and rank last in terms of priority for payment.

The above pyramid is a simplified example of a businesses capital structure. In practice, there can be many more different classes of bond in between each of the core categories shown above.

Where can you buy gilts and corporate bonds?

Gilts and corporate bonds are most cost effective to acquire via execution only investment platforms, though can also be acquired via advisory or discretionary brokers.

Investing in individual gilts / corporate bonds

Platforms such as Hargreaves Lansdown and Fidelity offer private investors the ability to invest in individual gilts and corporate bonds on the secondary market. However, unlike share purchases, individual gilt and corporate bond investments typically feature a minimum investment of £1,000.

This minimum investment value means that smaller investors would typically be better served choosing to invest via a bond investment fund or ETF in order to diversify their holdings and reduce the risk of one bankruptcy having a material impact on total portfolio value.

Investing in bond funds or ETFs

Bond funds hold extensive portfolios of underlying bonds and are typically available in both income or accumulation share classes to suit your investment goals.

A bond ETF tracks an index of bonds and tries to replicate its returns, and can be traded like shares throughout the day. Bond ETFs often only hold the most liquid bonds in the underlying bond index.

By investing in bond funds or ETFs, you will automatically get access to a diversified portfolio of bond instruments. There is generally no minimum level of investment, making adequate diversification easily obtainable for smaller investors.

Again, investors can make investments in bond funds or ETFs via execution only investment platforms like Hargreaves Lansdown or Fidelity.