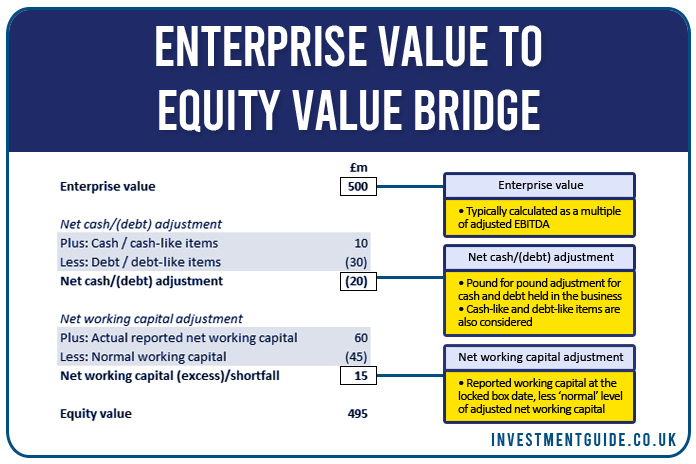

The Enterprise Value to Equity Value bridge is the most important concept in transaction purchase price calculations. The key point to understand is that transactions take place on a cash-free debt-free basis and with a normal level of working capital.

This means that the headline price agreed for the business is:

- Uplifted pound for pound by cash and cash-like items held by the business

- Reduced pound for pound by debt and debt-like items held by the business

- Adjusted for the difference between reported working capital and ‘normal’ working capital

Enterprise value

The enterprise value (‘EV’) is the headline price agreed for the business, typically based on a multiple of adjusted EBITDA (earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation).

The multiple a purchaser agrees to pay will be based on a number of factors such as security of future earnings, industry growth potential/risk, potential synergies, and the competitiveness of the sale process.

Enterprise value is important, but it does not represent the ultimate price paid by the purchaser. That price is the ‘equity value’ which takes into account the timing of the transaction. Without these adjustments, the purchaser would getting a better or worse deal at varying points in time.

Enterprise value may also be calculated using a discounted cash flow valuation. In the event that this type of valuation method is used, it’s important to note that any future cash-flows considered in that calculation should not be adjusted again in net debt.

For example, lets imagine that there was a cash outflow required to settle a legal case. That cash outflow was factored into the forecast model which formed the basis of the discounted cash flow calculation. On the balance sheet, there is a provision for the settlement proceeds in working capital. Ordinarily, you would take strip this out of net working capital and make a definitional net debt adjustment. However, in this situation, you would still not treat the provision as a normal working capital item, but you would not make a net debt adjustment as this would be double counting the deduction.

Net cash/(debt) adjustment

The purchaser pays for cash and debt pound for pound. Certain cash and debt items are widely accepted as debt (third party loans, accrued interest, overdrafts) and cash (free cash) though other items can be considered cash-like or debt-like and it is these items that are often hotly debated in negotiations.

Cash-like items

In regards to cash, consideration should be given to whether the cash in the business is readily available for withdrawal (i.e. free cash). Where cash is trapped (e.g. stuck in a foreign jurisdiction or subject to penalties for withdrawal), then the purchaser may not wish to make a pound for pound value adjustment.

Cash-like items are not necessarily ‘cash’ in nature, but could be considered cash-like for the purposes of equity value adjustments. Examples of cash-like items may include:

- A fixed asset not routinely used by the business. For example, if an owner-managed plumbing business owned a property unrelated to its business which was not revenue generating, that asset could be sold and the value of said property could be regarded as cash-like.

- A deposit paid by the business for an asset which is no longer required and will be refunded.

Debt-like items

Balance sheet items such as third party debt, bank overdrafts and any corporation tax liability are treated as reported debt on the balance sheet. These are easy to identify given they are on the face of the balance sheet. However, there are often debt-like items hiding within net working capital or not reported on the balance sheet.

Examples of potential debt-like items include:

- Provision for legal expenditure or settlement

- Related party loan balances

- Transaction related liabilities e.g. fees payable to banks/lawyers

- Capex underspend

- Unfunded pension liabilities

- Finance leases

- Derivatives

- Invoice discounting/factoring

- Change of control costs

- Deferred consideration

- Bonuses payable

- Deferred income (where not ‘normal’ and not expected to reoccur)

- Deposits

The classification of debt-like items such as those above is highly subjective and the treatment will depend upon the specific nature of the items.

You should typically consider:

- Has the item been considered as part of the calculation of enterprise value? I.e. was it incorporated into the EBITDA multiple or incorporated in the DCF calculation?

- What is the likelihood that the cash-flow will take place, and what is the likely timing?

Where the cash cost is not taken into account as part of the enterprise value calculation, this is an indication that the item should be treated as a debt-like item. Similarly, if an item is due to crystallise into cash in the short-term, this would be supportive of an adjustment.

Working capital adjustment

The level of working capital in any business fluctuates over time, from day to day, month to month. If no working capital adjustment was included as part of the closing mechanism, then one of either the buyer or seller would be disadvantaged.

For example, if lower than normal working capital was transferred to the buyer, the buyer would need to inject further capital. If higher than normal working capital was transferred, then the buyer would benefit as that working capital crystallises to cash.

How to calculate the net working capital adjustment

The working capital adjustment is calculated as the difference between ‘Adjusted NWC (after definitional adjustments, but before pro-forma adjustments)’ and a target level of working capital.

The target level of working capital is often calculated as the average adjusted NWC balance (after both definitional adjustments and pro-forma adjustments) over the trailing 12 month period. Often, but not always. It is also possible to set a target level of working capital based on other periods such as the last 6 months, 6 months actual + 6 months forecast, or even 12 month forecast. This choice of reference period can have a significant impact on value, which is why it’s often a hotly debated point in closing mechanism negotiations.

Reported working capital typically comprises trade and other receivables, trade and other payables, accruals, deferred income and stock.

Definitional adjustments are those were specific balances which sit within working capital are adjusted. This might include the removal of exceptional/one-off items, or the reallocation of debt-like balances. An example of a definitional adjustment would be the reallocation of a legal provision from NWC to debt.

A pro-forma adjustment would be a more hypothetical adjustment where judgement is applied to calculate an indicative working capital figure. For example, if there is evidence of creditor stretching and a pro-forma adjustment is made to reflect normal credit terms.